As a cooperative itself, Oikocredit recognizes the impressive capacity cooperatives such as Agricultural Company Cornesti have for supporting entire communities. This cooperative has been an Oikocredit project partner since 2005 when it received a loan of 155,000, followed by a second loan of 300,000 in 2008 to purchase farming equipment.

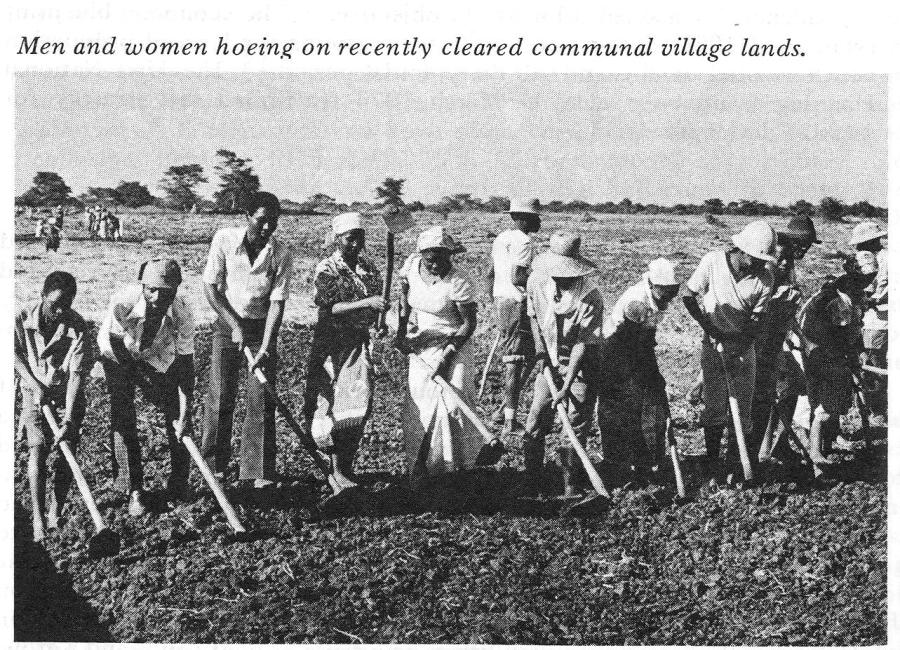

Traditional means of financing have been out of reach for Agricultural Company Cornesti, meaning Oikocredits loans have enabled the cooperative to buy much needed farm equipment to improve working conditions and productivity on the Cornesti farms. In future, the cooperative aims to have enough capital to build silos to store their produce to sell when the market is most in the farmers favour. Other cooperative members produce wheat, maize, barley, soy and sugar beet for both the members and for sale, while oats, potatoes and lucerne (also called alfalfa) are produced exclusively for members. Mr Palfi tends to the animals and crops on his land himself his primary crop being corn. One of those members is 80 year old farmer Alexanaruc Palfi. Since its beginnings, the cooperative has built up a solid member base of 500 people and almost all of those members are from Cornesti a town with a population of less than 1,500 people. The cooperative covers 845 hectares of farmland, all of which is privately owned by members while the assets of the cooperative are common property. Each member has one vote on major cooperative decisions, while seven elected individuals make up the cooperatives board. Today, members of Oikocredits partner Agricultural Company Cornesti maintain their own fields. Many farmers had spent years working in state-run collective farms, where workers received a standard pay, worked together on one large plot of land yet had no choice in their work and no say in farming operations. They planned to work again as a collective, but with a significantly different outlook than before. In 1991, in the small Romanian village of Cornesti, Transylvania, farmers came together. After the collapse of the communist regime, farmland was returned to its original owners and soon collectives began to reappear this time, collectives were characterized with an autonomous, democratic model where farmers gained control of their livelihoods.

While cooperatives were based on group work and shared benefits, membership was forced. According to the official propaganda they were essential tools in modernising agriculture.Until the Iron Curtain was lifted in 1989, Romanian farms were government owned and run as collectives. represented another method of cheating the farmers. Until they were dissolved in 1959, Machine-Tractor-Stations, Horse-Stations etc. During the decade after World War II their situation was usually better than in kolkhozes, later both were more or less the same. Sovkhozes (Russian советское хозяйство) were state owned estates with hired agricultural workers receiving regular wages. Many kolkhozes could not distribute anything at all and in the early 1950s collective farm earning in kind constituted on the average approximately 20 percent of the income of kolkhoz members. The profit left over from the state’s share was distributed among the members. The work was done according to previously confirmed (often impractical) economic plans. inhabitants of a certain region (from a few dozen to few thousand) were jointly involved in agriculture, whereas the land and all machinery belonged to all as well. ‘Although enterprise privatization reform had some effect on the performance of state and collective farms, independent. ‘Each year woman, children and even competing small farmers are forced to harvest the crop on big collective farms.’. Kolkhozes (Russian коллективное хозяйство) were collective farms, i.e. A jointly operated amalgamation of several small farms, especially one owned by the government. Soviet agriculture maintained different methods of production.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)